Content warning: this article includes mentions of murder, poisoning, self harm, and mental health issues.

Many say that the links to Lowell through the people, places, and things that we encounter in the larger world are a regular occurrence. In some cases, Lowell plays a prominent role in a given story within history. This is particularly true for the story of a woman who’s been labeled “the American Lucretia Borgia” or just simply “Jolly Jane.”

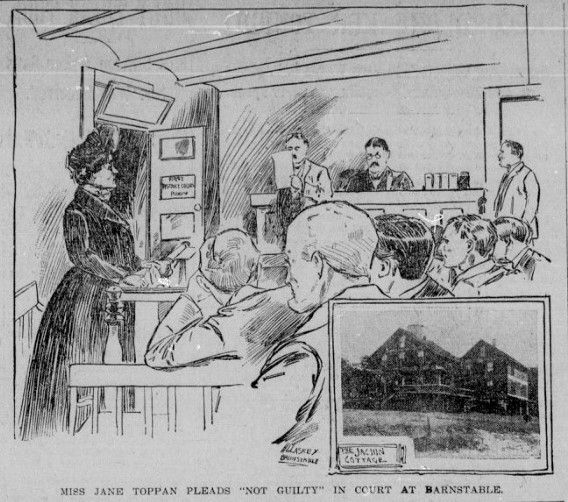

Image appears in the Lowell Sun,

November 1, 1901, pg. 1

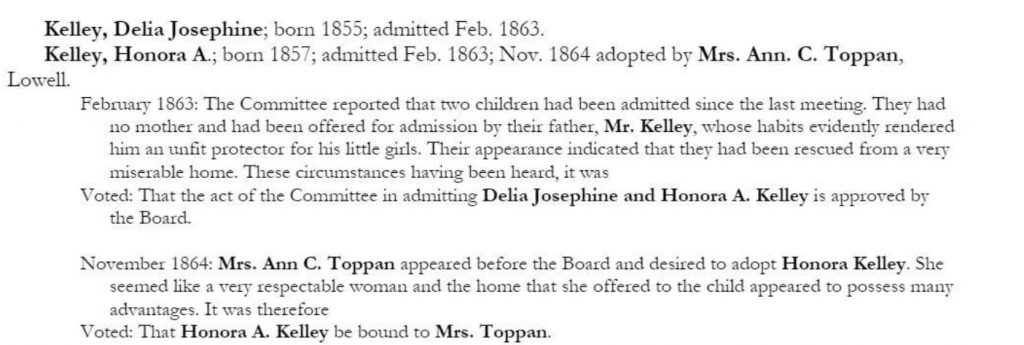

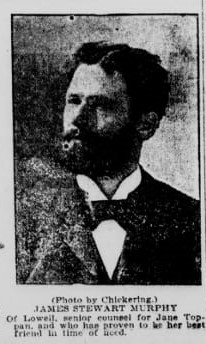

Jane as she was known in adulthood, started her life as Honora A. Kelley, the daughter of Peter Kelley and Bridget Finn. The date of her birth is listed on various documents as March 31, 1854, but this conflicts with other primary sources like the Boston Female Asylum and various census records, where her year of birth is attributed as closer to 1857. The youngest of 3 or 4 daughters, Honora lost her mother to consumption (tuberculosis) very early in her life. Archives have shown that Honora at least had 2 older sisters, Ellen “Nellie” and Delia. A Mary Kelley appeared in the papers after Jane’s arrest as talking about being the child of the Kelleys, but no recording of the birth was found [1]. Various rumors have been printed in papers about her father including that he was known as “Kelley the Crack” as in crackpot and that he was a tailor who attempted to sew his own eyelids shut. In February 1863, Mr. Kelley approached the Boston Female Asylum for admission of Honora and her slightly older sister, Delia Josephine. It was noted that Mr. Kelley will ill-equipped to deal with his youngest daughters and “whose habits evidently rendered him an unfit protector for his little girls. Their appearance indicated that they had been rescued from a very miserable home” [2]. After a few years, Mrs. Ann C. Toppan of Lowell appeared before the Board and desired to “adopt” Honora, and in November 1864 the committee approved to have Honora bound to Mrs. Toppan. According to Dr. Henry R. Stedman who evaluated the killer during the trial, Honora was six at the time she came to live with the Toppans, and she was “apprenticed to Mrs. T. on indenture papers” [3] Little documented information exists about Honora’s older sisters and father after she entered the Asylum, but comments appearing in the papers believed that Delia became an alcoholic and sex worker, while another sister, Nellie, was committed.

Starting in 1865, Honora took on the new name of Jane “Jennie” Toppan and appears as such in various censuses from that time on in Lowell. Never formally adopted, Jennie as she was known in her younger years attended Lowell Public Schools, “proving intelligent and quick to learn” [2] and supported the household through work. She lived in the Centralville area with Mrs. Toppan and her foster sister, Elizabeth, whom it appears that she befriended. There are stories that in order to hide her Irish heritage since there was still a stigma in the city from being so, a story was created by the Toppan family about the loss of her parents on an ocean crossing from Italy. Jennie was recalled as being a regular gossip, fabricator of untruths, and much more, though she had a charming nature. During interviews with Henry R. Stedman, M.D., she admitted that “she told many tales which we knew to be sheer inventions, among them, a story of her parentage, her alleged father having in reality lived in China for two years before her birth; another, of her horror of the dead which was so great that she sometimes fell senseless at the sight of dead bodies.” [2]. It is Stedman’s belief that “until [Jane] was a woman, she was under good moral and religious influences, home surroundings and discipline and had good associates, but her incorrigible propensities for deceit, falsehood, and trouble making, never absent from the first” [2]. There are other stories about Jennie having a beau who agreed to marry her around her 16th year of age and giving her a ring in the shape of a bird. Soon after, he moved out west to find work and fell in love with his landlady’s daughter and sent the bad news back to Jennie that he was calling off the engagement. Rumors abound that she destroyed the ring and this may have begun Jane’s spiral into darkness.

On her 18th birthday, Mrs. Toppan gifted Jane $50 and encouraged her to find her way in the world [4]. For a time, Jane stayed on in the household as help leaving the household at the age of 25 [4], but Stedman recounted that Jane provided “too much to content against, and her mother finally refused to let her remain longer in the family” [2]. In the late 1880s, she began her career as a nurse first at Cambridge Hospital, then as Massachusetts General Hospital, and then after being dismissed, returning again to Cambridge, where she was finally let go. She was quite skilled in taking care of patients, and had a pleasant demeanor earning her the nickname of “Jolly Jane” but in reality, she didn’t really like to work. Her mischief making of her early years continued in the hospital environment. It has been reported that her fellow workers were concerned about Jane because of “her unfounded and absurd suspicious, tale-bearing, slanderous gossip, and consequent mischief-making, as well as her pleasure in inventing fabulous tales” [3]. Various sources have mentioned that she misreported information, removed patients to other institutions, prolonged the illness of our favorite patients by reporting symptoms that did not happen. “During her term of service at one of the hospitals many articles were missed: sums of money, stationery, aprons, uniforms, etc., and she was suspected of stealing them, but her friends spoke so well of her and she was so adroit that the suspicion went no further, in spite of the evidence against her. During her residencies, she experimented on patients with morphine and atropine and seeing what happened to the patients. In administering medicines, she was extremely reckless and frequently gave larger doses than had been prescribed. Even at that time she was often to say that there was no use in keeping old people alive (a favorite sentiment with her since). She was also fond of asking about poisonous drugs and their antidotes… she was at that time, and has often since been, suspected of the opium habit, because of her strange conduct” [3]. There were also rumors that she’d poison patients, and if she was willing, bring them back from the point of death time and again. There was even one victim who lived that recalled Jane climbed into bed with her as she lay dying, before being interrupted by another nurse walking through. Due to her questionable conduct including dosing patients incorrectly and mishandling opiates, she was eventually discharged from both hospitals without ever graduating from their training programs.

Soon after leaving the hospitals, Jane entered into private nursing, where she was valued and very successful in being seen as liked and trusted in the care of family members. Many experienced physicians recommended Jane to families in need of assistance. Even though there were instances of theft, not returning borrowed money, and other issues, many families still felt Jane was a competent and caring nurse. Unfortunately, this persona as well as her propensity for stealing, desiring items that didn’t belong to her, and her general selfish nature led to the demise of many Massachusetts residents.

Throughout the years, Jane appeared to kill for a variety of reasons including opportunity, frustration, to clear a debt, employment, marriage prospects, and more. No one was safe from her desires. She killed a friend for a position at a theology school, her foster sister, her housekeeper and her brother-in-law’s sister in an attempt to become the mistress of the household, and other times, just because she could. Jane was known for dosing her victims with morphine, atropine or strychnine. Typically, she gave the morphine with a fatal dose of atropine in Hunyadi water, which was generally accepted by both patients and doctors alike. The bitterness of the poisons were covered by the Hunyadi water, which was used as a curative.

Whether it was pride or determination to clear her debts, the demise of Jane’s run as a serial killer started with the death of Mrs. Alden P. Davis. Mrs. Davis came to Cambridge to collect a debt for rent for time that Jane spent summering in Cataumet. Mrs. Davis had a mishap down a flight of the stairs trying to get to Cambridge to confront Jane for owed rent. Though injured, Mrs. Davis insisted on making the trip to settle this account. Once with Jane, Mrs. Davis collapsed and after Jane’s “nursing” succumbed within 2 days. Jane travelled with the body to Cataumet, where she interacted with the Davis married daughters, Mrs. Genevieve Davis Gordon and Mrs. Mary Davis Gibbs, as well as the widower Davis. Possibly trying to ingratiate herself into becoming the next Mrs. Davis, Jane spent time ‘helping the family’ and within a few short weeks, both daughters and Mr. Davis were deceased. Also, during her time in the home, three mysterious fires occurred with all being doused without much destruction. The youngest daughter, Mary, was in fine shape leading up to her death and had interacted with her father-in-law while her husband was at sea. After her death, Captain Gibbs started to question the demise of this entire family and began asking questions to everyone about the unlikely situation, following up with the police until an inquiry was undertaken. He surmised that Jane must be suspected of something as she was the only person in the household to make it out alive. After much pushing by Captain Gibbs, eventually the bodies of the Davis family were exhumed, examined, and poisons were identified. The police investigation began in earnest.

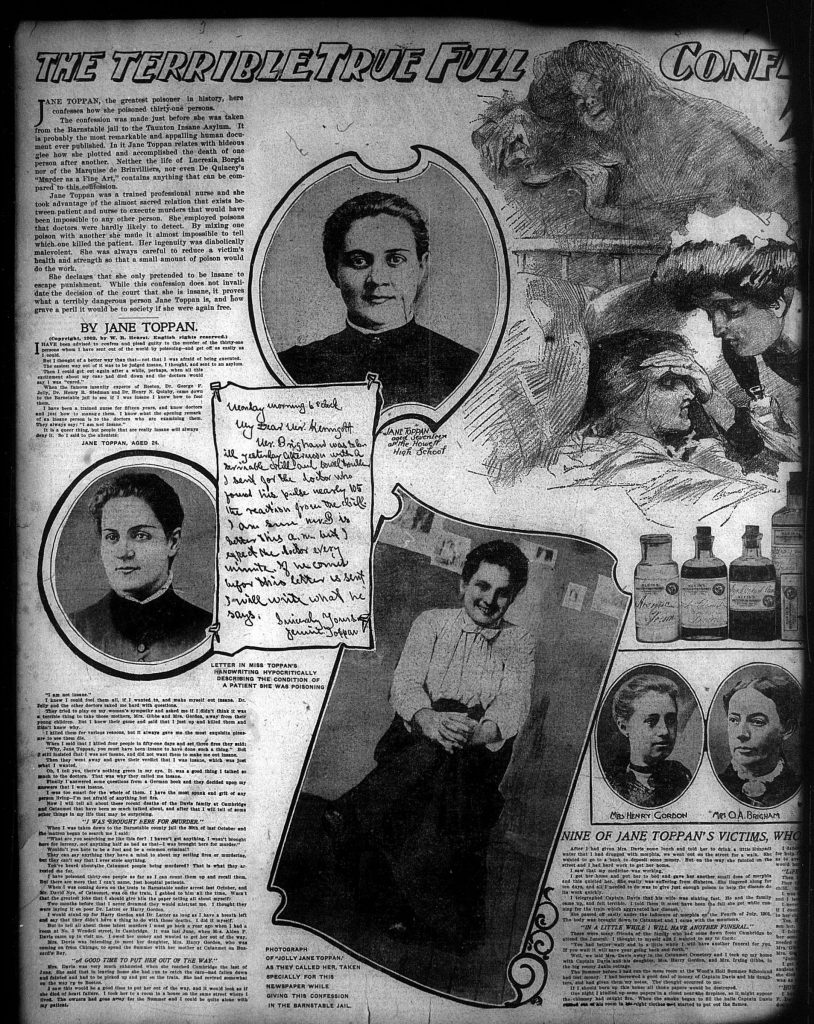

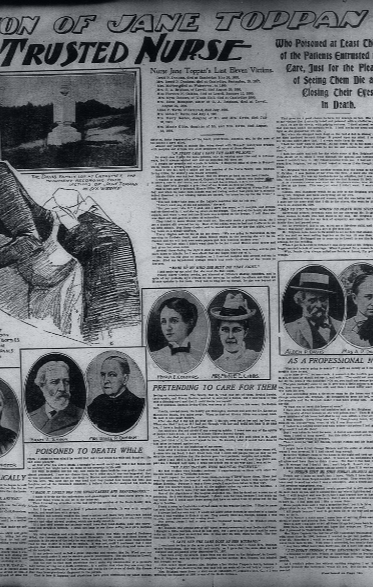

Photo in the Boston Sunday Post,

November 3, 1901, pg. 9

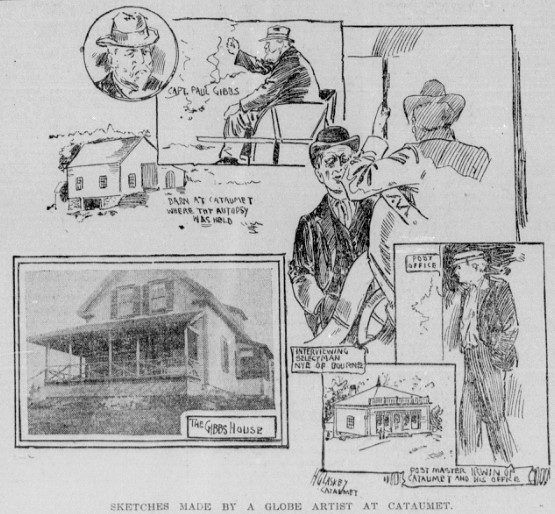

Soon after the death of Mrs. Gibbs, Jane returned to Lowell in an attempt to woo her brother-in-law, O.A. Brigham. It is believed that Mr. Brigham was poisoned and then treated by Jane in an attempt for her to be kept in his good graces. During that time, Brigham’s sister, Mrs. Edna Bannister, died of heart failure. Mr. Brigham’s frustrations with Jane and her complicating nature to his household led to him asking her to leave by the end of September 1901. As a result of this request, Jane attempted to end her life by giving herself a dose of morphine. Dr. Lathrop who had recommended her in the past to families in need of a nurse was the regular physician in the Brigham household. After her self administration of morphine, Jane was treated at Lowell General Hospital, where she attempted to take her own life again. By this point, the detectives were in full investigation mode, and one of the detectives became a patient at Lowell General Hospital to keep an eye on Jane. After she was discharged, she travelled to Amherst, New Hampshire to visit with friends. It was there on October 29, 1901 that she was arrested. For much of the time after being arrested, Jane did not appear to be concerned about the outcome.

After being caught, Jane often lamented that her killing spree happened because she never married. “If I had been a married woman, I probably would not have killed all of those people. I would have had my husband, my children and my home to take up my mind.” This quote has been attributed to her confession in the New York Journal 1902.

Photo in the Boston Sunday Post,

November 3, 1901, pg. 9

Jane’s lawyer and the trial

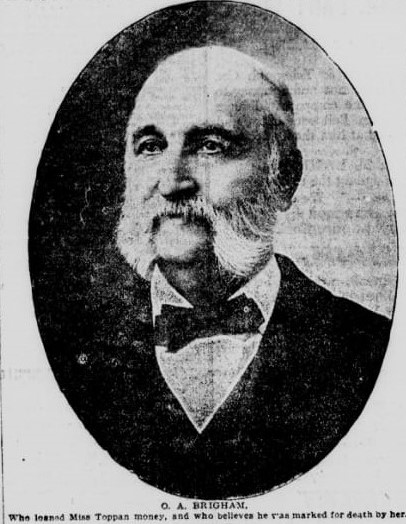

Upon her arrest for the death of Mary Gibbs, Jane was assigned an attorney, F.M. Bixby. Jane sent a request through the post that her childhood friend, James Stuart Murphy of Lowell to represent her. He was out of state when she was arrested and was surprised that her arrest was published in the paper. There were rumors written that Murphy was very friendly with Jane and perhaps even had a crush on her. He remained her friend even after her trial and eventual commitment to the Taunton State Asylum.

November 3, 1901, pg. 9

James Stuart Murphy was born in Quebec in 1860 and moved to Lowell in 1872. A graduate of Lowell Public Schools, Murphy entered the law office of the Honorable Joshua N. Marshall and attended Boston University Law School. He also did reportorial work for the Lowell Morning Times. He became a naturalized citizen in 1882. Admitted to the bar in 1885, Murphy was committed to public service, serving as a member of the Odd Fellows, Masons, and Royal Arcanum. He was also a member of the Vesper Boat Club. He served as a member of the Common Council 1889-1890. He was also a Massachusetts State Representative for District 22, Ward 2 of Lowell. He was a Republic and served on the House Judiciary Committee, as clerk for the committee on taxation as well as transit in 1894. He was married to F. Blanche Hard and raised his family until his passing in 1940. He is buried in Westlawn Cemetery. [8]

Jane served approximately seven months in jail leading up to her trial. She was indicted for three of the murders of the Davis family, but her trial was only for the murder of Mrs. Gibbs. Jane’s arrest and eventual trial became global news, appearing in papers as far away as Australia, New Zealand, and China.

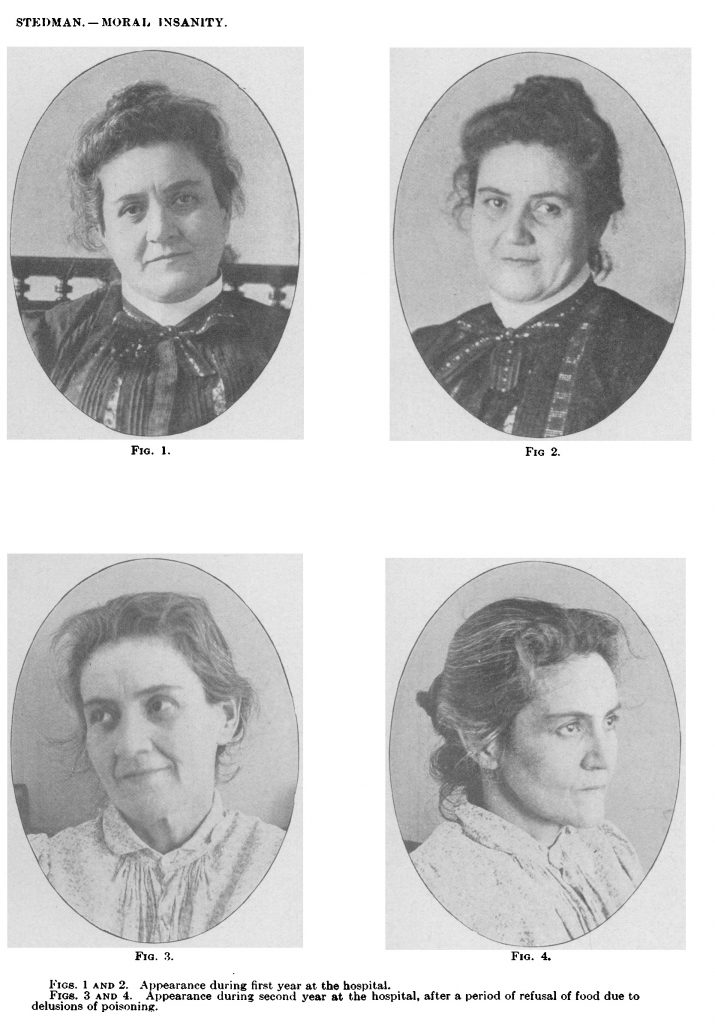

In March 1902, doctors, Henry Stedman, George Jelly and Hosea Quinby evaluated Jane and determined her to be insane. Her various confessions and Dr. Stedman’s thoughts on Jane can be found in his paper, “A Case of Moral Insanity with Repeated Homicides and Incendiarism and Late Development of Delusions,” which was published in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in 1904.

Jane’s trial can be found online at the State Library of Massachusetts. It lasted about 8 hours and the jury deliberated approximately 27 minutes.

Jane was happy to share with anyone that she wasn’t insane. She went along with the ruling as she believed that she would be able to be released in the future. Because she appeared to have a family history of mental health issues, it was argued that she likely was insane. Papers of the time reported that she admitted to Murphy that she was not insane and confessed to killing upwards of 31 confirmed murders, but it could have been as many as 100.

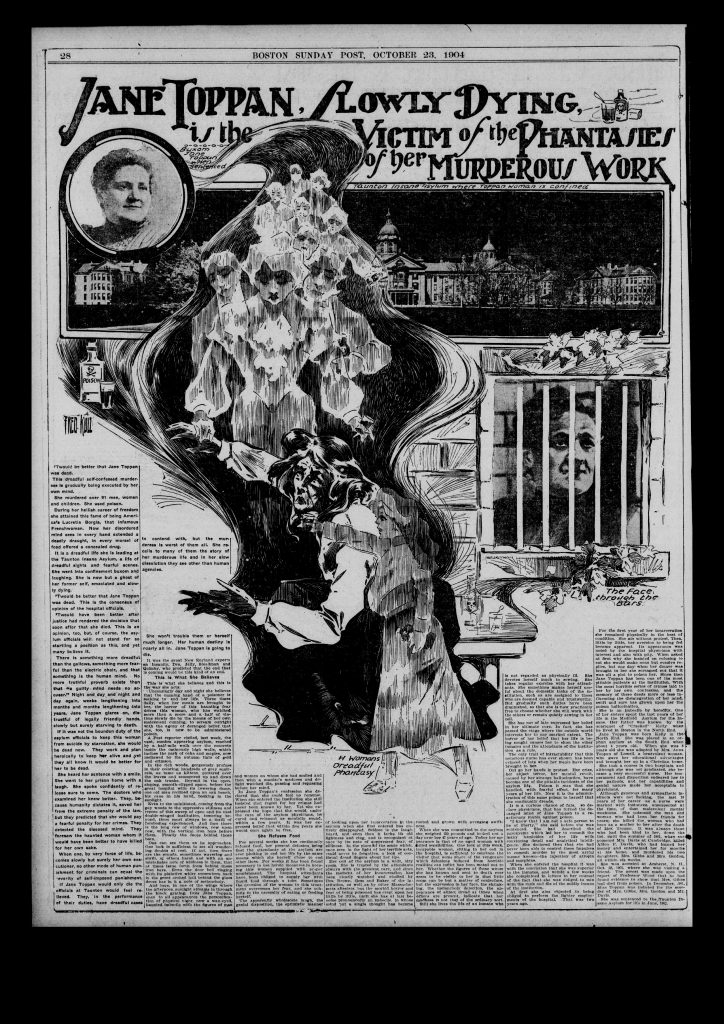

Jane was ultimately sentenced to Taunton’s Insane Asylum where she lived out her remaining days until her death. Many believe that she was never truly insane including her brother-in-law and Dr. W.H. Lathrop, but her time in Taunton definitely impacted her. She had a fear that her food was being poisoned and often did not eat. While she seemed to have her wits about her, time spent in this facility appeared to have aged her and had a negative effect on her outlook.

Murphy did not seem to face any disparagement for serving as Jane’s attorney. In fact, it is believed that he was the person who leaked to the press that Jane had committed more than 31 murders. It is said that William Randolph Hearst actually typed up Jane’s confession for his article in the New York Journal.

copy of the original New York Journal from 1902.

Jane’s Confirmed Victims [5]

Notes listed below are not included in the original article.

| Israel Dunham of Cambridge, died May 26, 1895, aged 83. Cause given, “strangulated hernia.” Ill four days. Jane Toppan nursed him | |

| Mrs. Lovely P. Dunham, wife of Israel, died in Cambridge Sept. 19, 1897, aged 87. “Old age.” Jane Toppan nursed her. | |

| Mrs. O.A. Brigham of Lowell, died Aug. 19, 1899. Two days illness. “Heart failure.” Jane Toppan was in the house when she died, and waited upon her as part of the time she was ill. [note: this was Jane’s foster sister, Elizabeth Toppan Brigham – in the paper she was incorrectly identified as Mrs. O.A. Bridgman. Elizabeth was 70 years of age at the time of her death.] |  [6] |

| Mrs. Mary McNear of Cambridge, wealthy widow, died Dec. 28, 1900, aged 70. Two days’ illness. “Apoplexy.” Jane Toppan nursed her for three hours before death. [note: Apoplexy is the state of being unconscious or an incapacity resulting from a cerebral hemorrhage or stroke.] | |

| Mrs. Florence M. Calkins, housekeeper for O.A. Brigham of Lowell, died Jan. 15, 1900, aged 45. Ill three days. “Heart failure.” Jane Toppan was in the house when she died. [note: It is believed that she was targeted as she was interfering with Jane’s ability to woo Mr. Brigham] | |

| William H. Ingraham of Watertown, died Jan. 27, 1900, aged 70. “Heart failure.” Jane Toppan nursed him. | |

| Miss Sarah E. Connors, matron of St. John’s Theological school refectory, died in Cambridge Feb. 11, 1900, aged 48. “Complication of diseases.” Under the care of Jane Toppan. [note: It is believed that Jane killed her to take her position at the Theology school where she worked. Miss Connors was affectionately known as Myra.] |  [6] |

| Mrs. Alden P. Davis of Cataumet July 4, 1901, aged 62. “Chronic diabetes.” Jane Toppan nursed her. | |

| Mrs. Genevieve E. Gordon of Chicago, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Alden P. Davis, died at Cataumet July 31, 1901. Short illness. No death certificate. Jane Toppan nursed her. | |

| Alden P. Davis, died in Cataumet, Aug. 8, 1901, aged 65. Few days’ illness. No death certificate. Jane Toppan nursed him. | |

| Mrs. Mary E. Gibbs, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Alden P. Davis, died in Cataumet Aug. 13, 1901, aged 40. Two days’ illness. No death certificate. Jane Toppan nursed her. |  [7] |

| Mrs. Edna Bannister of Turnbridge, Vt., sister of O.A. Brigham, died in Lowell Aug. 27, 1901, aged 77. Two days’ illness. “Heart failure.” Jane Toppan was in the house when she died. [note: Edna was Mr. Brigham’s sister who was visiting and was seen as a threat to Jane’s ability to stay in the house and attempt to become the second Mrs. Brigham.] |

Jane spent the rest of her life at the Taunton State Hospital until her death on August 22, 1938. She is buried at Mayflower Hill Cemetery in Taunton. She is buried in grave 984 in Section 34 in the Potter’s Field.

Jane Toppan & Lowell

For a concise summary of the many ways that Jane’s story is tied to Lowell, here’s a quick list

- Relocated to Lowell as a child into the Toppan household in Centralville

- Attended Lowell Schools – graduated Lowell High

- Appears in 1865, 1870 and 1880 Census as Jennie

- Listed in 1901 City Directory under Nurses

- Agreed to marry a suitor from Lowell who then fell in love with another when traveling for work and threw her over. Blames this as the start of her murderous ways.

- Murdered her foster sister, Elizabeth Stanford Toppan Brigham in 1899 while on vacation. Jane was listed in the probate records and received a gift through will distribution.

- Murdered the Brigham family housekeeper, Florence Calkins in 1900

- Alden Davis (whose entire family perished) worked on the Ladd & Whitney monument located in front of City Hall

- After the death of the Davis family, Jane returned to Lowell and moved in with Deacon Oramel A. Brigham, who she poisoned and nursed back to health to demonstrate her worth. It is believed that she wanted to marry him. Deacon Brigham was a deacon at the First Trinitarian Congregational Church and also worked a depot master for the Boston & Maine Railroad.

- With a few days of arriving, Jane poisoned Edna Bannister, the deacon’s sister and Elizabeth’s sister-in-law, who died 19 June 1901

- Due to the chaotic nature of Jane, Mr. Brigham asked Jane to leave. Over the next 2 days, she made attempts to poison herself with morphine and was nursed at Lowell General Hospital

- The Brigham and Toppan relatives are buried in Lowell Cemetery

- Her requested lawyer was from Lowell – James Stuart Murphy. They were childhood friends. He remained her friend after the trial and was assigned her guardian while at Taunton State Hospital (formerly the Taunton Insane Asylum).

- Oramel A. Brigham and Dr. W.H. Lathrop were called as witnesses, though other Lowell residents were considered.

Cited Sources & Other Materials Used

[1] – Associated Press (1902, March 28). The Toppan Case – Police Trying to Trace Woman’s Parentage. Lowell Sun, pg. 3.

[2] – Boston Female Asylum Records – https://openarchives.umb.edu/digital/collection/p15774coll8/id/322

[3] – Stedman, Henry R., M.D. (1904, July 21). A Case of Moral Insanity with Repeated Homicides and Incendiarism and Late Development of Delusions. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM190407211510301

[4] – 6:00 Edition (1901, October 31). Jane Toppan – Alleged Murderess Formerly Lived in Lowell. Lowell Sun, pg. 5.

[5] – (1902, July 27). Poison Her Passion, The Clinton Morning Age, pg. 3.

[6] – Associated Press (1901, November 4). Only One Charge Will Be Preferred Against Miss Toppan. Lowell Sun, pg. 1

[7] – Associated Press (1902, June 24). Jane Toppan. Boston Post, pg. 2

[8] – A Souvenir of Massachusetts Legislators. (1894). United States: A.M. Bridgman.

Commonwealth vs. Jane Toppan: before Braley and Bell, J.J. and a Jury – Barnstable Superior Court, 1902 – digitized by the State Library of Massachusetts – available at https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/734741

Newspaper Archive was invaluable for providing confirmation of various statements – papers used include the Lowell Sun, Boston Sunday Globe, Boston Daily Globe, Boston Post, Boston Sunday Post, and others listed above.

Suggested Readings

Fatal : the poisonous life of a serial killer / Harold Schechter.

Outlaw Women: America’s Most Notorious Daughters, Wives, and Mothers /Col. Robert Barr Smith

America’s first female serial killer : Jane Toppan and the making of a monster / Mary Kay Macbrayer