Here’s the latest “Forgotten New England” column from Lowell Historical Society Board member Ryan Owens.July 9, 2012

The Story of Lowell’s Shedd Park

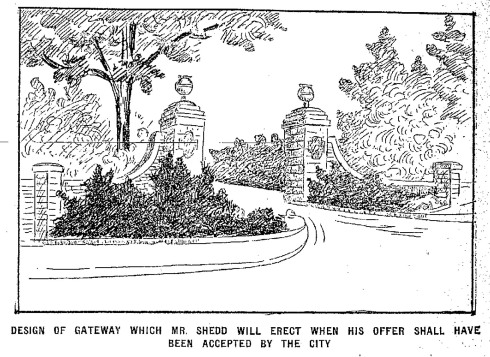

The gates are familiar to all who pass Lowell’s Shedd Park at the intersection of Rogers Street (Route 38) and Knapp Avenue in the city’s Belvidere section. And they tell a story of some of the greatest generosity ever experienced by the city of Lowell.

Today, Lowell’s Shedd Park is home to fifty acres of tennis courts, baseball diamonds, picnic areas, and a water spray park. Its pavilion is often used as a stage for public events and concerts. In the years surrounding the turn of the twentieth century, however, the land that eventually became the park was a combination of open fields and dense forests, and it was privately owned.

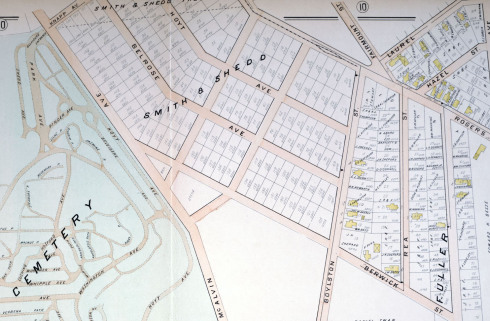

The land wasn’t always destined to become Shedd Park. As late as 1896, it was considered for subdivision and development into housing lots.

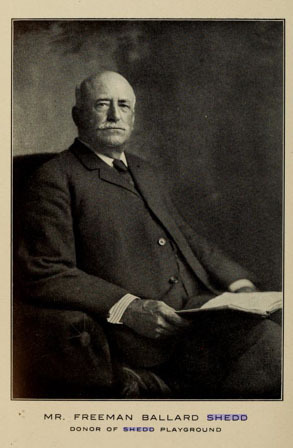

But, in the end, Freeman B. Shedd, the owner of the land, gave it as a gift to the City of Lowell, with no strings attached. On July 14, 1910, Freeman B. Shedd sent a letter to Lowell’s mayor at the time, John F. Meehan.

He said:

“I have acquired title to a tract of land containing fifty acres, more or less, which is situated south of Knapp Avenue and adjoining Fort Hill park, that I offer to the City of Lowell for its acceptance under the following conditions:

“First: That it shall forever be used as a park and recreation or playground for the citizens and children of the City of Lowell, and for no other purpose.

“Second: That no building or structure shall be erected on the land except such as is adapted and required for use in connection with said park and playground.

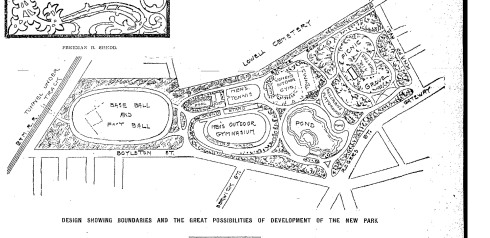

“Third: That the city will, within a reasonable time, proceed to develop and prepare the ground for such uses on the lines indicated by accompanying plan furnished by E.W.Bowditch, civil engineer of Boston.

“Fourth: That I shall have the right to erect, subject to the approval of the park commission, a suitable gateway and entrance, with a tablet or tablets thereon with the following transcription: ”Shedd Playground. A gift to the City of Lowell by Freeman Ballard Shedd, A.D. 1910.”

And, with that he closed the letter, and awaited the city’s response to his offer. Real estate experts of the day valued the land at $50,000. There were really no strings attached. Freeman Shedd, a lifelong resident of Lowell, and was simply and in the words of the day, an ‘ardent lover’ of his city.

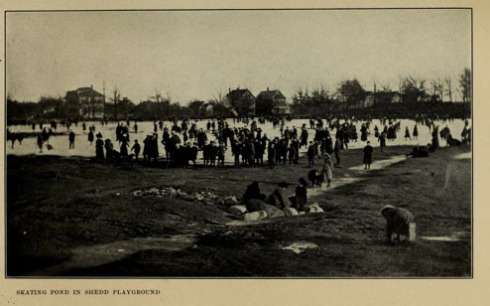

The vote to accept Shedd’s park was unanimous, and a rising vote of thanks was offered to Freeman Shedd. An appropriation of $10,000 was voted by the City Council on November 4, 1910 to clear the land and build a roadway to the entrance. Work commenced quickly. A roadway was built to grant better access to the future park. Ground was cleared; trees were felled. The skating rink was created. The Council intended, within 10 years to make the park one of the best outside Boston. Freeman Shedd again stepped forward to make that happen. Shedd’s will left $100,000 to the city for the development of the park, provided that his daughter, Mary Belle, left no descendants when she herself died. Mary Belle Shedd did, indeed, died childless in 1921, but was survived by Freeman Shedd’s wife, Amy. When Amy Shedd died in 1924, the $100,000 reverted to the City of Lowell and Shedd Park was further developed.

The original Bowditch plan for Shedd Park called for an open air theater, roughly where the little league baseball diamonds sit now along Knapp Avenue, a pond with a beach roughly where the Senior League baseball diamond sits now, and gender-specific gyms and tennis courts. A field designated for baseball and football was to reside further down Boylston Street, where the current picnic area is. Original plans also called for an underground tunnel to pass under the B&M railroad to connect the park with Wigginville, now better known as South Lowell.

In the last days of November and into early December 1910, a 6″ inch service pipe was laid into the park, and from it approximately four million gallons of water were let onto the land to flood about five acres of land for a skating rink. City residents loved it. The Water Department wasn’t so thrilled. Although the Park Department paid for the pipe and its installation, they refused to pay the water bill.

Outside downtown Lowell, there are few Lowell landmarks as universally well-known as Belvidere’s Shedd Park. At over 50 acres, the park is among the largest in the city. Its story, enhanced by generations of memories among Lowell residents, traces its origins to one of Lowell’s most generous sons, who grew up to leave Lowell’s one of its greatest gifts ever.